Too hot (enough to cook an egg out on the street), too wet - in a planet facing an 'extreme heat epidemic'

“Is that for real?” I messaged a Vietnamese journalist in my Facebook list in May, after seeing her reel that showed an egg being cooked in a frying pan laid out on the street, under the blistering heat.

Yes, Huynh Thao says, she filmed her mother’s neighbour doing this ‘cooking’. “I heard the sizzling sound,” she adde in the reel. Her neighbour said it took “about five minutes or more” to cook the egg along with a thin piece of meat. That day’s temperature? 41 degrees Celsius in Que Son district in central Quang Nam province.

That reel (screengrab above) was one of too many reminders that extreme heat has become a recurrent fact of life in a heated-up planet.

The rains have now come in parts of Southeast Asia, but rains too are connected to global heating. In the Philippines, where the extreme heat of summer made many hanker for the rains, the monsoon rains were exacerbated by a typhoon - which did not even hit land - and dumped the capital with over two weeks’ worth of rain in one day in late July.

Scientists have been watching how the planet’s warming affects storms, which hold more moisture as ocean temperatures rise and can then unleash this in rainfall. A warmer globe also means a more humid one (which can make a 36C reading feel like 45C). Every degree of global warming is projected to cause a 7% increase in extreme daily rainfall, the World Meteorological Organization says.

Stories about record-breaking hot days, months and years have been normal fare in the news.

22 July - and before that the day before - brought the planet to its highest average temperature ever at 17.15C in the WMO’s dataset. That figure is all the more astounding when one considers that this record was reached without heat-bringing El Niño. It is the highest daily average temperature since 2016. Also, the 10 years with the highest daily average temperature are the last 10 years from 2015 to 2024.

This year is expected to beat 2023 as the hottest ever for the planet.

May 2024 marked a full year of average reaching record highs, part of a global warming trend due to human activity mainly through greenhouse gas emissions, says the US’ National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA). “We’re experiencing more hot days, more hot months, more hot years,” said Kate Calvin, NASA’s chief scientist and senior climate advisor. (The last 10 years have also been the warmest since record-keeping began.)

Over the one-year period from May 2023 to May 2024, the world experienced, on average, 26 days of “unusually warm temperatures”, said the report ‘Climate Change and the Escalation of Global Extreme Heat: Assessing and Addressing the Risks’.

“This is not a surprise or an accident — the causes are well known and the impacts devastating. The continuous burning of coal, oil and gas has released enough greenhouse gasses to warm the planet by 1.2oC since pre-industrial times,” said the report produced by World Weather Attribution, Climate Central and the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre. “Year after year, human-induced climate change manifests through more intense and frequent extreme weather events, with heat waves being the most dramatically affected.”

Across Southeast Asia, this year’s summer felt like one unrelenting humid heatwave.

In March, thousands of schools in the Philippines resorted to remote learning because of heatwaves, with temperatures reaching 43.8 Celsius. The Cambodian newspaper ‘Thmey Thmey’ posted photos of teachers having students sitting in class with moist towels over their heads. Vietnam’s hottest temperature hit 43.2 C this year, just a bit lower than last year’s highest-ever reading of 44.2 C. In Myanmar, record-breaking temperatures added to the woes of those displaced in the country’s civil war.

EXTREME HEAT TWICE AS LIKELY

“Human-caused climate change is boosting dangerous extreme heat for billions, and making heat events longer and more likely,” concluded the same report on climate change and extreme heat.

The study, which identified 76 extreme heat waves across 90 countries between 15 May 2023 and 15 May 2024 (including in Southeast Asia). found that:

About 78% of the global population, or 6.3 billion people, experienced at least 31 days of extreme heat “that was made at least two times more likely due to human-caused climate change” (extreme heat means ‘hotter than 90% of temperatures observed in their local area over the 1991-2020 period’)

Human-caused climate change added an average of 26 days of extreme heat than there would have been without a warmed planet

Analysing the report’s data for Southeast Asian countries, the region showed an average of 84.5 days of extreme heat than there would have been without the influence of climate change. Singapore has the most number of extreme heat days added at 147 - or nearly five months in a year, followed by Brunei and Indonesia.

In its earlier report on heat waves in 2022, 2023 and this year in West, Southeast and South Asia, World Weather Attribution also said that human-induced climate change has been increasing the likelihood, length and intensity of heatwaves.

By how much? The difference in the usual likelihood of such events and this year’s extreme heat in the Philippines, for instance, “is so large that the (2024) event would have been impossible without human-caused climate change”, said the May report by World Weather Attribution, a group of scientists that analyses the role of climate change in extreme weather.

On any given year, the chance of such an event happening in the Philippines is around 10% or once every 10 years under the recent El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) conditions - and once in 20 years overall without the influence of El Niño.

The increase in the intensity of such events in the Philippines due to human-induced climate change is about 1.2°C. El Niño did make this year’s heatwave warmer, but by just about 0.2°C. (This useful visualisation, created by data journalist Prinz Magtulis, followed the Philippines’ extreme heat in April.)

Extreme heat kills, and is now “a global health emergency” and there is in place a Global Heat Health Information Network. Heat stress is “the leading cause of weather-related deaths” today, says the World Health Organization. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said: “Billions of people are facing an extreme heat epidemic -- wilting under increasingly deadly heatwaves, with temperatures topping 50 degrees Celsius around the world.”

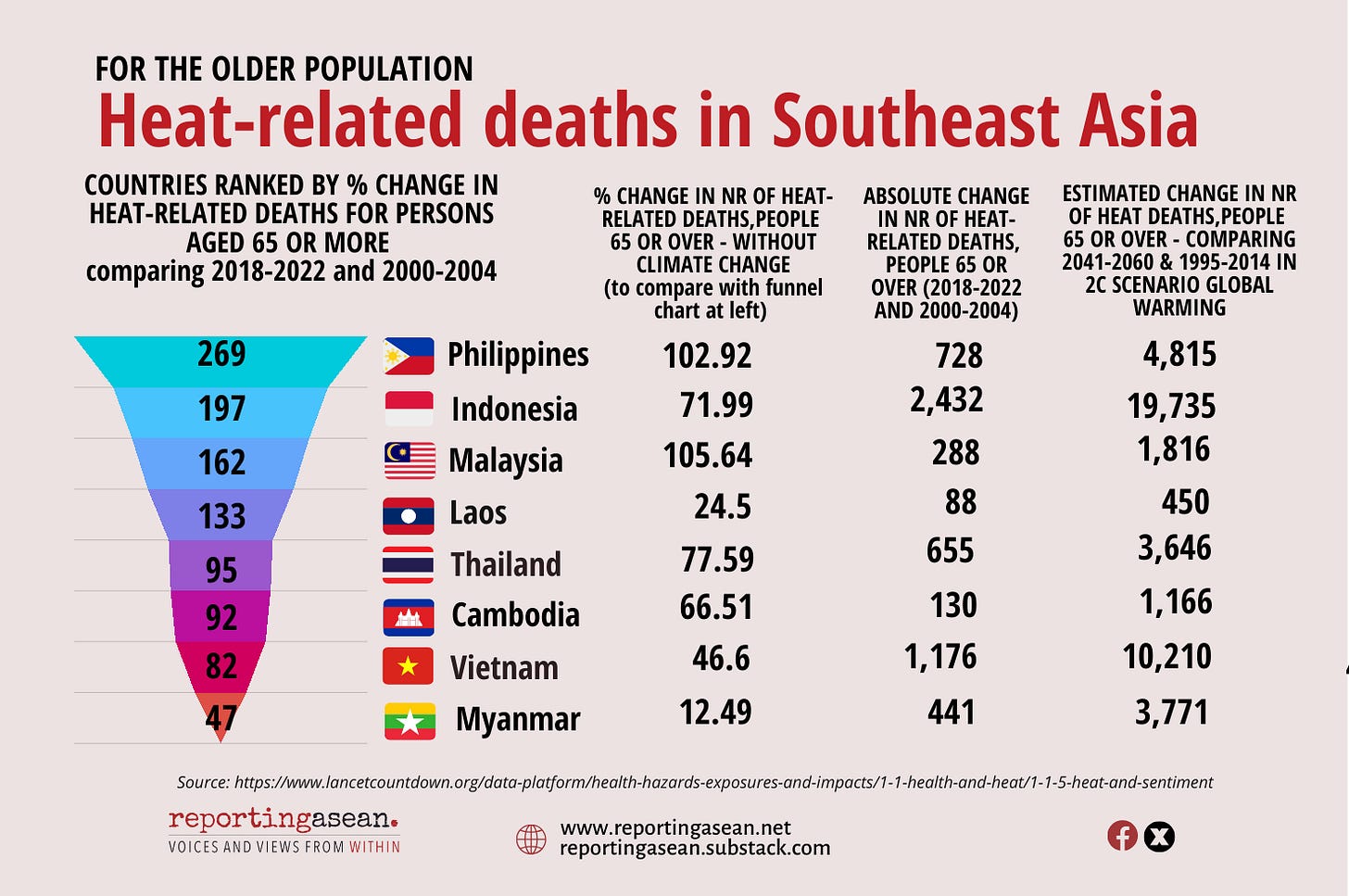

Across the world, there has been an 85% hike in heat-related mortality for people over 65 years of age between 2000 - 2004 and 2017-2021, reports the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Projections . It projects higher increases in the coming decades.

In Southeast Asia, the Philippines with the highest percentage of change (269%) in heat-related deaths for people aged 65 and over, when comparing the two time periods above. The visual below shows the regional data extracted from the global dataset.

Heat is the most deadly extreme weather phenomenon today. At particularly high risk from extreme heat are children, older adults, people experiencing homelessness, those with chronic illnesses, those who work outdoors, low-income as well as marginalised communities,

Heat-related illnesses and effects - which causes humans’ core body temperatures to rise perilously high - can include headaches, dizziness, muscle spasms, and dizziness, dehydration, heat stroke, the worsening of chronic conditions and death. Humans’ core body temperature has a very narrow range, close to 37 degrees Celsius.

Hotter times point to the need not only for ways of living with this reality but for pragmatic actions that make sense in developing-country settings.

Extreme heat can feel even more punishing in Southeast Asia’s dense megacities and urban areas, because they are home to urban heat islands with concrete, steel and buildings in areas that have less greenery.

WE PAY ATTENTION TO STORMS, BUT WHAT ABOUT THE HEAT?

Yet heatwaves often don’t get the same responses and public awareness drives as other events. “Although floods and cyclones make more headlines, heat is arguably the deadliest extreme event, with thousands of extreme heat-related deaths reported each year and many more that go unreported,” the World Weather Attribution said.

Disaster coordination and monitoring of disasters typically covers storms and floods, earthquakes and fires, not always heatwaves.

While heat-related deaths in Southeast Asia were reported this summer, public awareness of these do not rank as high as deaths from storms, floods or quakes. Heat-related deaths are often under-reported, as many experts say. (The Thai health ministry reported 64 heat-related deaths in 2024, up from 37 last year. )

In 2023, Singapore released a national heat advisory to alert people, especially when doing outdoor activities. Singapore’s heat stress advisories are in an app and on the national meteorological service’s website, showing readings of Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WGBT). More than heat index (‘feels-like’ temperature plus humidity), WGBT is the more accurate data for how being outdoors feels, as it takes into consideration not only temperature and humidity, but wind speed and solar radiation.)

The Philippines’ weather agency Pag-asa halted its heat-index updates as the rainy season set in in June.

Heat-related deaths occur not only from heat stroke or during heat events. Extreme heat causes premature death, mostly from conditions cardiovascular disease, respiratory infections or diabetes that hotter temperatures worsen or make people more vulnerable to, as researcher Hannah Ritchie of One World In Data says in the platform’s dataset of deaths from extreme temperatures.

“Think about someone dying from extreme temperatures. You probably pictured someone passing out from heat stroke or dying from hypothermia,” Ritchie wrote. “But this is not how most people die from ‘heat”. They die from conditions such as cardiovascular or kidney disease, respiratory infections, or diabetes.”

“Almost no one has ‘heat’ or ‘cold” written on their death certificate, but sub-optimal temperatures lead to a large number of premature deaths,” she added. (OWID says that historically, more people around the world have died from colder temperatures but that this trend may now change with a heated planet.)

Monitoring methods and definitions of heat-related illnesses and deaths can also vary, and one could ask if these figures could, or should be, redefined as ‘disasters’ in disaster counts. In many studies, heat-related deaths are defined as those where exposure to high temperatures were the cause of mortality or significantly contributed to it.

SENSIBLE SOLUTIONS - AND YES, PLANTING TREES

Calls have been rising for countries to think up smarter, realistic ways to deal with hot days and give people better skills to cope with these. News reports showed us how communities in Southeast Asia tried to coped, from the opening of cooling venues as heat shelters to providing free water to the public.

But because the heat is not going away, top-priority attention needs to go beyond extreme heat events to sound longer-term interventions, from better tracking data about heat, heat mapping in our megacities to putting in place safety policies about school and work (especially outdoors) all the way to how homes and buildings are built.

These approaches have to be rooted in developing-country realities such as the fact that many of the region’s city residents live in informal settlements, often in homes built from materials that trap heat.

Some coping methods were discussed at the Global Summit on Extreme Heat, organised in March by the US Agency for International Development and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

In India, groups like the Mahila Housing SEWA Trust provide roof coverings to outdoor vendors, most of whom are women. Other ideas range from painting roofs green or lighter colours to reflect heat as well as to reduce power bills, and replacing homes whose calls and roofs are made of corrugated-iron sheets and become ovens in the heat.

Sensible solutions like planting trees go a long way to make cities more liveable, the mayor of Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown, Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr, told the heat summit. Since its ‘Freetown the tree town’ project started in 2020, the city - which has a chief heat officer - has planted 977,000 trees as of March and aims to hit its target of 1 million trees later in the year.

Each tree is tagged during its three-to-five year growth period. A total of 1,500 young people are employed to regularly upload photos of the trees they look after, Aki-Sawyerr says.

These days, reports of extreme heat have been coming from other parts of the world - more than 1,300 people died due to the heat in the Hajj pilgrimage, wildfires are back in Canada and the United States, and Japan is having sizzling summer.

Released ahead of the Paris Olympics, the ‘Rights of Fire’ report warns of risks to athletes from extreme heat - noting that the average temperature in Paris has climbed by 3.1 C since 1924, the last time the French capital hosted the games.

But while the seasons change and Southeast Asia is seeing wetter weather now, the signs are all too clear that extreme heat and its impacts are now our reality.

As Filipinos yearned for rains - even typhoons - to ease drought, Filipino climate researcher Maria Laurice Jamero asked: “Will we ever experience a normal, neutral state again -- instead of just swinging from one extreme end to the next?”

In a LinkedIn post soon after early rains came, she wrote: ”In the meantime, life goes on somehow... But make no mistake, this is NOT resilience. So often, we see a beautiful picture and think maybe it's not so bad after all. But in reality, this is us making do, this is us holding out for something better, this is us SUFFERING.”

Thanks for reading!

Johanna -founder/editor of the Reporting ASEAN series

2 DATA BOX

3 FEATURES

Cambodia: Young Enough To Drink

WRITTEN BY JOHANNA SON, REPORTING FROM CAMBODIA BY MENG SEAVMEY AND MECH CHOULAY *

At 17, Kun Thea (not her real name) is a veteran when it comes to drinking alcohol. She started drinking at 14 or 15, with a cocktail with less than 4% alcohol content at a family party. Soon, she moved on to drinking beer.

There were times when her parents would not allow her to drink, but “the consumption kept going because it became a habit for us to drink during parties,” said Kun Thea, who lives in Cambodia’s southern Takeo province.