What Myanmar has to do with Gaza, why we need to care about Myanmar, and a Palestinian story

Myanmar and the occupied Palestinian territory, which Gaza is part of, stand close to each other at the top of the lists of crises in 2024.

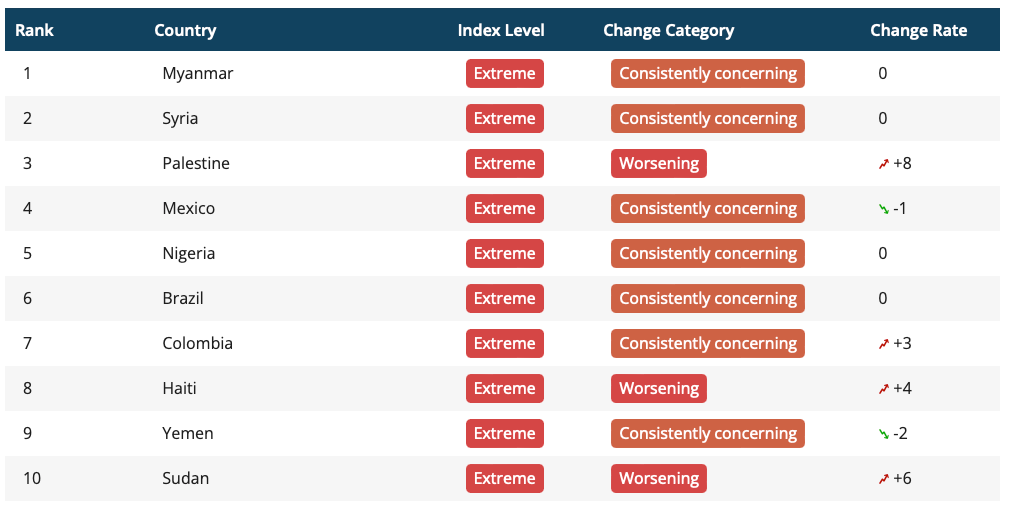

Myanmar, which has just marked the third anniversary of the 1 February 2021 coup, is first in the list of 50 most violent countries in the ACLED Conflict Index (with “extreme, high, or turbulent levels of conflict”), shown in the screenshot below. Palestine is third, after Syria.

In another crisis list, the 2024 Emergency Watchlist of the International Refugee Committee, the occupied Palestinian territory ranks second (after Sudan), and Myanmar is fifth in a ranked list of 10 countries.

In various databases, the differences between lists and rankings vary in the aspect of violence each conflict has more of. But all human suffering is suffering, and there is too much of it - and now with Gaza - in front of us and on our screens, in our psyches, in a world jolted by witnessing its own dark sides.

“Of those 50 countries, Myanmar is the most violent overall and retains its position as the most ‘fragmented’ due to its hundreds of small militias formed to contest the government since the coup in 2021,” according to the January brief of the ACLED Conflict Index. “Syria is the second most conflicted country due to multiple, overlapping conflicts which continue to occur within its borders. Palestine has conflict covering almost all of its territories and therefore ranks as the most ‘diffuse’ conflict.”

“Myanmar is the sole Asian country with extreme violence, but it remains the most difficult conflict case in the world,” ACLED pointed out.

Many have described the escalation of armed conflict in Myanmar since October 2023 as bringing in the best prospects yet for the defeat of the armed forces, even as this has caused the number of displaced people to surge by 628,000 at end-2023 (to over 2.6 million).

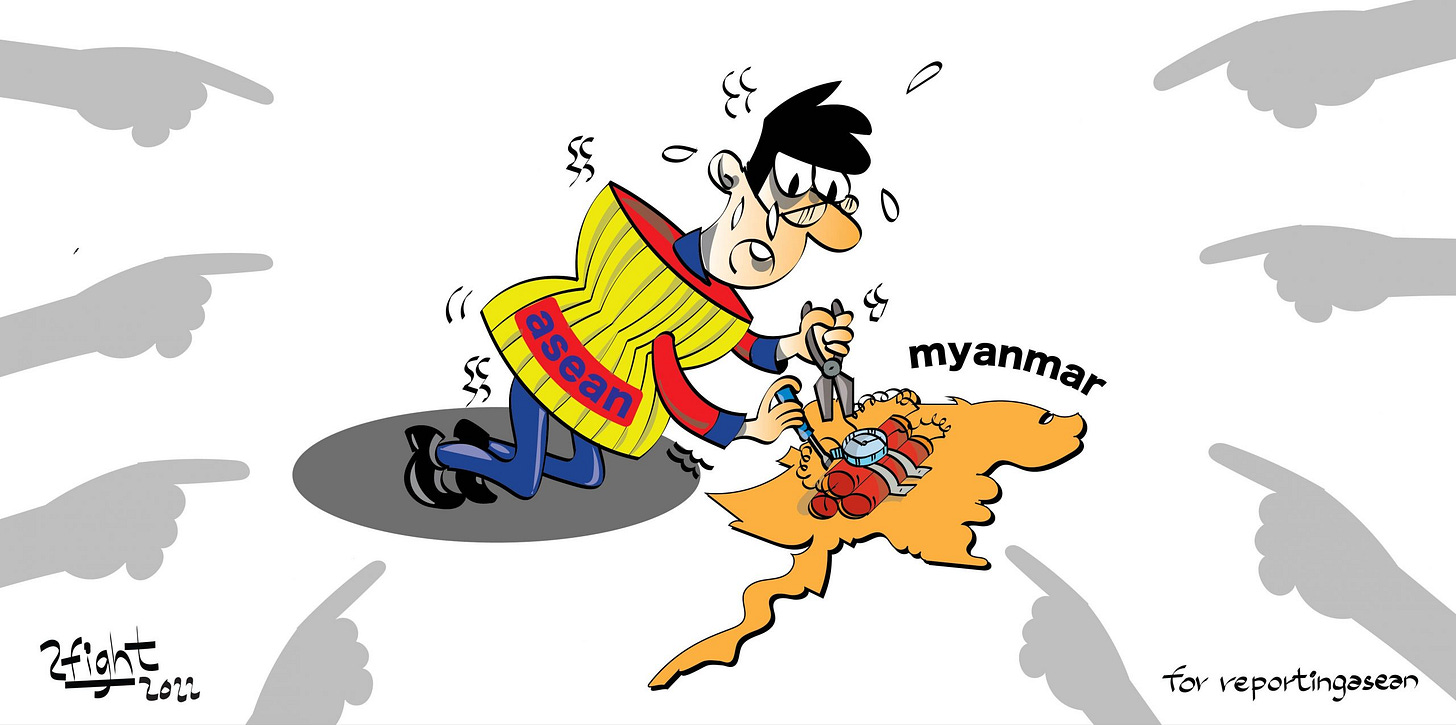

Myanmar’s conflict, like Sudan, have been among the most violent countries for some time but often fall out of the international media’s radar. “Many conflicts do not garner sufficient attention, no matter how violent,” said the ACLED note.

There is another angle from which Myanmar has something to do with Gaza - and this gets complicated.

These days, Myanmar is often seen amidst its post-coup polycrisis and the resistance against the military junta. But the long-running struggles of its Rohingya minority continue - and a reminder of these injustices emerged during South Africa’s presentation of its case against Israel at the International Court of Justice.

When South Africa’s legal team spoke before the Court in January, its members cited - many times - The Gambia’s earlier genocide case against Myanmar for its actions on the country’s Rohingya community. “In The Gambia vs Myanmar. . .”, we heard again and again during three-hour session.

In these two genocide cases before the ICJ, the accused are the states - Israel and Myanmar - charged with persecuting, killing and destroying, with genocidal intent, minority communities that are/were inside the borders of these nation-states, namely Palestinians in Gaza and the Rohingya in Myanmar. (We did a slide deck comparing the ICJ provisional orders to Israel and Myanmar here - there were similarities and some differences.)

One in a set of 8 slides looking at the ICJ’s provisional orders in the genocide cases against Israel and Myanmar.

The Rohingya case was brought to the World Court two years after the Myanmar military launched scorched-earth operations that drove some 700,000 Rohingya to flee from western Rakhine state to neighbouring Bangladesh in 2017.

Today, over 1 million Rohingya refugees live in the world’s largest refugee camp in Bangladesh. Some 600,000 remain within Rakhine, “where they continue to suffer severe rights restrictions and the threat of further violence”, the UN said. Nearly 4,500 Rohingya tried to flee the refugee camps (and a fewer number, Myanmar) in perilous boat journeys last year, resulting in one Rohingya reported to have died or gone missing for every eight people who go on such journeys, it reported.

These two peoples’ struggles have been around for decades. Most of the Rohingya are stateless, which sets them aside from other refugees. There is a State of Palestine that is a “non-member observer state” of the United Nations, but one whose its territories are listed as occupied by Israel.

The plight of the Rohingya remains a pending challenge for Myanmar in a post- military context, when the country’s National Unity Government (NUG) says it will put in place a “federal democracy” that respects its ethnic diversity.

Myanmar’s politics are part of the Rohingya case too. The Myanmar that was charged in 2019 was the pre-coup one, led by the National League for Democracy party that was later overthrown. State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, who has been in detention since the 2021 coup, appeared before the ICJ in December 2019 to defend the Myanmar state against accusations of genocide.

The view of the Rohingya as outsiders (called ‘Bengali immigrants’ and excluded from the state’s official list of ethnic groups) has been a mainstream view in Myanmar through decades, and this is also why it remains a touchy issue for a future federal democracy. However, there have been remarks about recognising the persecution of the community and some apologies since the coup.

After the 2021 coup, Myanmar’s military regime, called the State Administration Council, appeared before the ICJ to argue that the genocide case be dropped. In February 2022, the NUG, which has been working for international recognition, said it accepts the ICJ’s jurisdiction over the case. The military regime continues to interact with the Court, including making submissions.

Our interview on the Myanmar’s coup anniversary is below. Meantime, going back to Gaza – a contributor writes about how the horrors there, far away from Southeast Asia, are prodding her to dig deeper into her Palestinian identity.

Finally, the year of the wood dragon (the lunar new year starts on 10 Feb) is supposed to be about more humanitarian values, harmony and flexibility, I read somewhere.

May this fiery dragon chase out occupation, colonialism and conflicts -

Johanna Son, founder/editor of the Reporting ASEAN series

1 Myanmar on Our Minds

‘What we can all do is to keep the attention on why we all still need to care about Myanmar’

A Reporting ASEAN conversation with Moe Thuzar, coordinator of the Myanmar Studies Programme at the ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, on the third anniversary of the February 2021 coup.

2 Views and Points

A Journey Back to Myself, Amidst Gaza’s Pain

BY YUJIN

“It’s complicated,” Papa has said a couple of times in recent weeks, when I ask about what’s happening in Gaza. Sometimes, though, he doesn’t reply much to my questions. Is he is avoiding having to talk about painful things?

3 S is for Sustainability

INDONESIA: The Last Fisherwomen of Halmahera?

BY ADI RENALDI

Small fisherfolk fear that they are losing out in nickel mining boom, which Indonesia sees as key to being a lead player in the global energy transition.

Visuals around sustainability

4 Data Box - (links to useful data sources)

Data for Myanmar

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

Momentum from Operation 1027 Threatens Military Rule

Resistance to the Military Junta Gains Momentum - Conflict Watchlist 2024

International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Myanmar Conflict Map

Myanmar Peace Monitor

Myanmar Witness

Data for Myanmar and Gaza